CAREC Health Website – How We Did It: One Health in Georgia

How Georgia Embraced a One Health Approach

One Health is a deceptively simple idea: human, animal, plant and ecological health challenges are all interconnected, and can only be effectively addressed in a holistic way. However, putting that idea into practice is not simple at all, and entails bringing together sectors that traditionally have not worked together, do not understand each other, and may not even really respect each other’s unique skill set.

The need to take a unified approach to human, animal and ecological health is becoming all the more pressing, as zoonoses–human diseases of animal origin–are becoming increasingly common, and as environmental degradation continues to profoundly affect human and animal health.

One Health is a conceptual framework that enables these three domains to work together, and adopt a collaborative mindset. Using a One Health approach enables the three sectors to deal with shared threats more effectively than if each sector tries to deal with it alone. One Health has attracted attention worldwide, and is gaining traction, led by the United Nations Quadripartite consisting of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), World Health Organization (WHO) and World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH).

Communication, coordination, collaboration

At country level, putting the One Health approach into practice demands a high degree of communication, coordination and collaboration, not just across multiple disciplines, but also between different levels of government, and with the private sector, the scientific community and other stakeholders.

Many Asian Development Bank (ADB) developing member countries (DMCs) have declared an interest in pursuing One Health approaches to a wide range of human health threats, including antimicrobial resistance, pandemic threats, food security and safety, and even to individual diseases such as rabies. However, there are a few countries that have gone further than most in incorporating One Health concepts into, for example, bio-surveillance and biodefense. In the Central and West Asia region, one of the countries that stands out in this regard is Georgia.

As is often the case, in Georgia, it was the country’s human health sector that took the initiative to introduce One Health approaches. In 2018, with strong support from the leadership of the Communicable Disease Department at the National Center for Disease Control and Public Health (NCDC) the One Health Division was established. Although the One Health team already had strong connections with public health colleagues, the challenge was how to connect and collaborate with their colleagues in veterinary and ecological health.

Finding a place to start

One entry point to this was through the NCDC’s Richard Lugar Center for Public Health Research, one of the strongest public health laboratories in the Caucasus region. A zoo-entomology laboratory, it has capacity to collect and study disease vectors such as ticks and mosquitoes, as well as rodents and other zoonotic disease reservoirs. However, interaction between zoological and human epidemiologists was not incentivized. In any overlapping projects, there was a prevailing culture in both human and veterinary sectors of addressing zoonotic threats as an exclusive issue of their own respective areas, without sharing their unique context, perspective and expertise with each other. This was a missed opportunity to collectively discussing the matter.”

As a result, while discussions about zoonotic diseases were happening at the regional level in the health sector, there was a missed opportunity to have that conversation with regional veterinarians too. For example, when NCDC conducted refresher training on zoonotic diseases all around the country, there were no municipal or regional zoologists or veterinarians participating, and no information sharing between them. The One Health approach enabled better communication between human and veterinary epidemiologists, so, for example, zoo-entomological surveillance field trips could be better planned to target areas where humans are affected. It also promoted joint education activities.

National plan of action

This turned out to be a good place to start, but it became clear that enduring, systemic change would need a national plan of action. There were governmental and ministerial decrees that regulated information exchange between the human and veterinary sectors, and an electronic surveillance information system to exchange information between the two sectors in real time, but there was much room for improvement by applying a One Health approach.

The NCDC’s One Health Division began by reviewing literature and other countries’ success stories taking parts of their action plans and strategies that looked relevant to Georgia’s context, and achievable. Then in 2021, the UN Quadripartite published its global One Health Joint Plan of Action (2022 – 2026), which the One Health team then went about adapting to Georgia’s unique, national context. At the same time, the global momentum around One Health helped to build the bridges of communication with the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture, and other relevant national entities including the National Food Agency and the State Laboratory of Agriculture, which were already involved in One Health-related activities such as disease surveillance.

In 2023, the Government of Georgia published its One Health National Action Plan 2023-2025. The plan began as a bottom-up approach, but once it was approved by the government, it became top-down too, with objectives and actions that different institutions are tasked to achieve. Whilst some of the plan’s objectives are only of public health or veterinary sector interest, overall, by looking through a One Health lens, all three sectors are motivated to look at what they are currently doing, and examine what can be improved.

Steps to success

As well as buy-in from senior leadership in the health ministry, who recognized that One Health was part of a broader process of health systems strengthening and improving health security, one of the key success factors to bringing a One Health approach to Georgia has been the efforts of individual One Health champions within the different government bodies, who socialized the idea and went out of their way to connect with the counterparts in the other sectors.

Another key factor was that the action plan does not entail requests for request additional funds from the ministries involved, although it may require them to change how some existing resources are allocated. The One Health National Action Plan 2023-2025 also leverages some of Georgia’s existing obligations to galvanize support within the ministries. For example, in November 2023, the European Commission issued an official recommendation to grant Georgia candidate status for European Union membership. This entails meeting certain requirements across the three domains covered by One Health.

Using a One Health approach

One of the most pressing issues in Georgia that a One Health approach can help with is antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which relates to both the human and veterinary sectors. In the mid-2010’s Georgia introduced an electronic prescription system, which enables monitoring of prescription practices, and reveals irrational antimicrobial prescribing practices in the country. However, without One Health approach, it will be very hard for AMR to be controlled in the country. Globally the veterinary sector is known to be by far the bigger consumer of antibiotics, for example. In Georgia there is not the same level of information and transparency about veterinary use of antibiotics as there is for human use.

The One Health action plan encourages the necessary multi-stakeholder collaboration to tackle what is a delicate issue, because controlling irrational antibiotic use in animal husbandry necessitates engagement with the private sector, and reconciling the human health impact of antibiotics with their use in livestock for commercial reasons.

Other than AMR, the NCDC One Health Division has identified numerous disease threats that are best tackled with a One Health approach, including anthrax, rabies, brucellosis, Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever, Q-fever, leptospirosis and leishmaniosis.

Regional health security

Having a One Health strategy is also helpful to Georgia in terms of meeting its commitments to regional health security, because it can address emerging or re-emerging cross-border disease threats. Certain diseases, such as dengue fever, have been circulating in the region more frequently than previous years, and the country’s One Health Committee (which was being formed at the time of writing) will likely have a task of reviewing such threats and then developing recommendations for relevant sectors on how to lower the risks.

Georgia’s example offers useful lessons to other countries pondering how to go about introducing a One Health approach. Georgia has shown that it is possible to start small and at the grassroots, convening like-minded people across the three sectors, and building channels of communication. This lays groundwork for future, bigger steps, and adapting global best practice in a pragmatic, context-specific way.

Written by Jane Parry. With thanks to Lela Sulaberidze, Head of the Strategic Development and Analytics Department Ministry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Labour, Health and Social Affairs of Georgia, and Giorgi Chakhunashvili, Head of One Health Division, Communicable Disease Department National Center for Disease Control and Public Health (NCDC), who provided invaluable information for this article.

To find out more, contact:

Lela Sulaberidze, Head of the Strategic Development and Analytics Department

Ministry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Labour, Health

Social Affairs of Georgia, and Giorgi Chakhunashvili, Head of One Health Division, Communicable Disease Department National Center for Disease Control and Public Health

Field testing for Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever in Samtskhe-Javakheti, Georgia. Photo credit: Giorgi Chakhunashvili

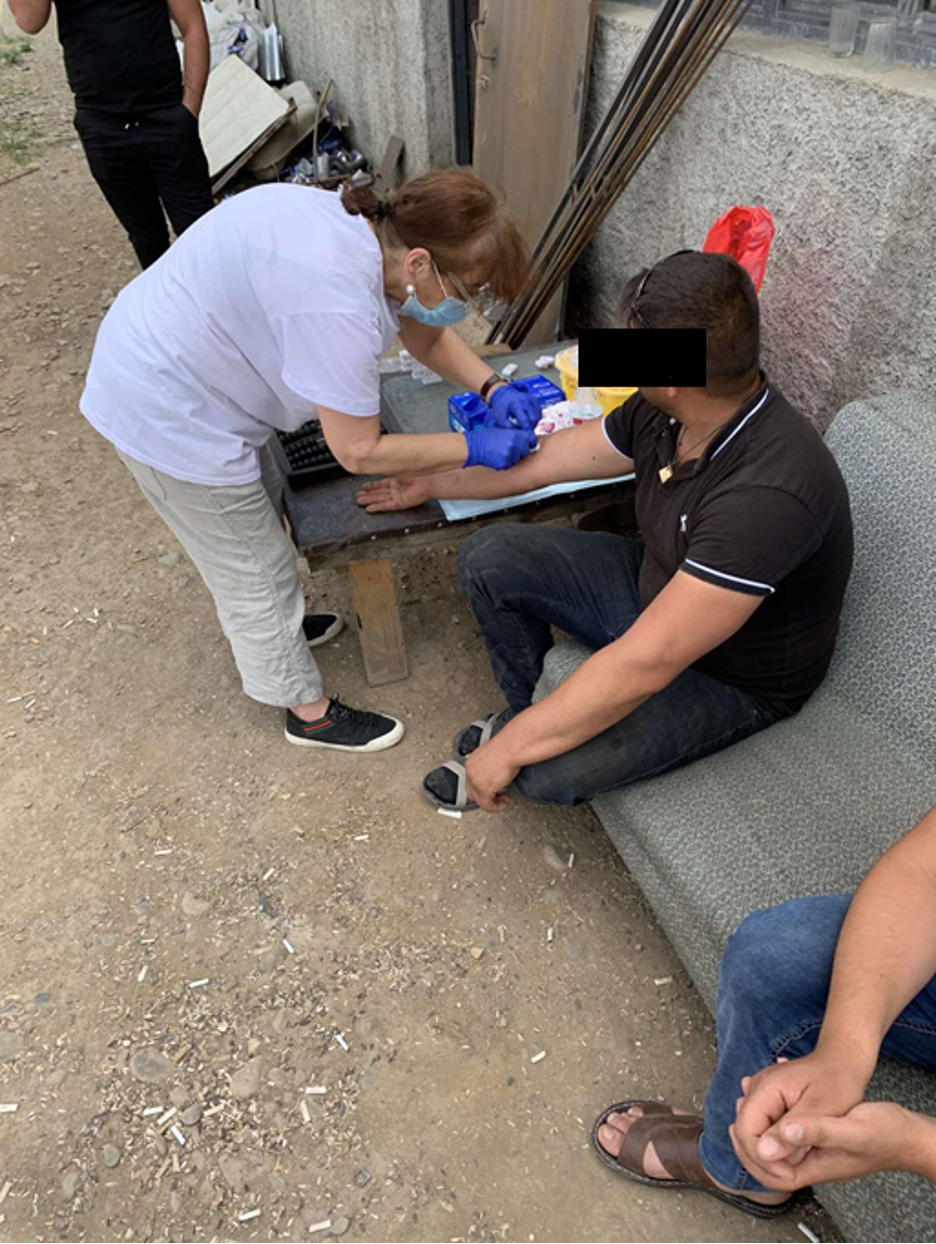

Farm workers in Kakheti region being tested for Q fever. Photo credit: Giorgi Chakhunashvili